Our Church is Shrinking

“Our church is shrinking,” said the head elder, “and it’s your fault.”

Zeb didn’t respond immediately. He’d been summoned to the church board meeting, though when he’d used the word “summoned” the head elder had objected. “We just want to talk to you,” he had said. But it felt like a summons, and this felt like a trial, only less organized.

“Well,” said the head elder after the silence had grown uncomfortable. “Do you have anything to say?”

“I’m not sure what makes you believe it’s my fault the church is shrinking.”

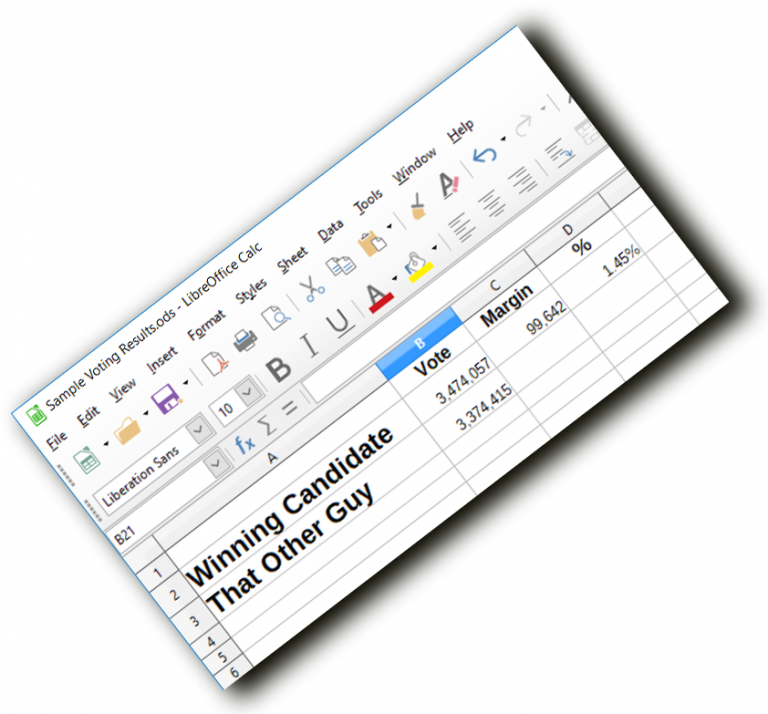

“It seems obvious to me. We hired you to make this church grow, and now a year has passed, and we’ve lost more members this year than ever before, and of those that have joined the church not one—not one!—has stayed.”

“But this church has been shrinking for more than a decade, and shrinking faster each year. How does it become my fault?” Zeb looked truly puzzled.

“A year ago we took a big risk,” said another man, a businessman who also acted as church business manager. “We decided that we could afford to hire a pastor of outreach to stop the bleeding. But spending all that money on your salary has proven a bad investment.”

“Yes,” said another, “and you missed our last planning meeting as well.”

“I did send an e-mail to let you and the pastor know I wouldn’t be available.”

“Yes, an e-mail! I didn’t get it until after the meeting. But that meeting was important! Even critical! You had known about it for weeks. You shouldn’t have missed it.”

Zeb really couldn’t argue here. He’d chosen to drive a homeless man to the shelter. He’d sent an e-mail because he knew they wouldn’t get it in time and so they wouldn’t be able to order him to attend the meeting. He really could have gotten someone else to drive the man to the shelter. But he just couldn’t face that meeting.

“So you see,” said another, “we gambled on you and it looks like we lost.”

“I see,” said Zeb. Then he paused for more than a minute. People started shifting in their seats in discomfort as the time extended, but it did look like Zeb was gathering his thoughts.

“I’m afraid I’ve been operating under false pretenses,” he said finally. “The only excuse I can give is that I didn’t know it. But I should have. I should have known what you were doing.”

“What do you mean ‘what we were doing?'” asked the head elder. “We’re talking about you.”

“I’m wondering if you have the letter you sent describing this job.”

“I can’t say that I have a copy,” said the head elder. “Why?”

“Well, I can’t recall anything in there that said I was supposed to make this church grow. If I had seen anything like that, I wouldn’t have applied for the job. If I’d suspected anything like that was in your mind, I would have never taken it when it was offered.”

“But we hired you as outreach pastor!” The head elder was somewhere between shock and anger.

“And if you expect an outreach pastor to ‘grow your church,’ then you’re badly mistaken. I can’t grow your church and neither can any other person you might hire.”

“Don’t pretend that everyone is as incompetent as you are,” said the businessman.

“Incompetent? I suppose I deserve that. I should have realized just what you were up to long ago and done something about it. But I was so happy to be doing outreach and getting paid for it, I didn’t realize.”

“You keep saying things like, ‘what we’re up to,'” said the head elder. We’re not “up to” anything, except that we expect you to do your job.

“But you didn’t include ‘make our church grow’ in your job description.”

“I’d think it was obvious.”

“Oh, but it isn’t. In fact, it’s obviously wrong!” There was a gasp in the room. One didn’t tell the head elder he was wrong in that direct a way.

“So what do you think your job is?” asked the head elder after he’d recovered enough. He was sure they were going to fire this guy before the meeting was over.

“Well, the description you provided in your letter said things like ‘building the kingdom of God in this community’ and ‘reaching the lost for Christ,’ not to mention ‘leading the congregation in showing Christ’s love.’ I have tried to do those things with God’s help.”

“But if you had been doing all that, our church would have grown!” said the businessman. “As it is, few enough people visit, even less come back a second time, and the two families who did join left the church in a few weeks. So somewhere in there you’re not doing your job.”

Zeb tried hard to stay calm, but with that last line something broke in him. He had always wondered if there was such a thing as righteous anger, and he was in enough control to wonder if his anger right then was righteous or not.

“I think I can explain that,” he said in clipped tones.

“I’d really like to hear it, said the businessman before Zeb could continue.

“I really doubt you do,” said Zeb, and continued before he could be interrupted. “I remember each and every person I’ve brought to this house. One man came to church in jeans and a t-shirt. One of you told him he wasn’t dressed appropriately, and should make sure to wear appropriate clothing next time he was in church ‘out of respect for God,’ was the phrase, I believe.

“He didn’t own any better clothing, so he just never came back. Fortunately, I found him another church that was willing to let him attend in whatever clothing he had. Well, actually, the members got together and found him a new wardrobe. He has a job now as well.”

“But you’re supposed to be bringing people here!’ exclaimed the businessman, “You’re not hired to grow other churches.”

“I did bring him here, in case you hadn’t noticed. I’d even talked to some members and started to collect clothes for him. But you ran him off before I could finish.”

The businessman was red in the face and opened his mouth to respond, but Zeb just rolled right over him.

“Then there were the Jeffries. Their family actually joined the church, but one of you caught Mr Jeffries having a beer and told him he was misrepresenting Christ and the church by drinking. He decided he’d rather be somewhere else. But you see, nobody had told Mr. Jeffries that people at this church don’t drink beer.”

“You should have taken care of that,” said the head elder, just short of shouting.

“True, but you see, I can’t find anything in the stated beliefs and practices of this church that says one can’t have a beer. It’s just sort of something you do. Or don’t do.”

“So,” said the businessman, “you’re saying we’re running people off.” He was a practical man.

“Yes,” said Zeb, “you’re running people off.”

“I think you’re bringing in the wrong people,” said the head elder.

There was silence. Nobody wanted to put it that explicitly. The head elder had spoken without really thinking. It was something you did, but not something you named.

“I think,” said Zeb, “that the only honest thing for me to do is give you my resignation. The job you hired me to do can’t be done by someone hired. It has to be done by the whole church. And as it is, I wouldn’t want to do it. I don’t believe there are any wrong people. That you think there are”—he looked straight at the head elder—”is something I believe you should make a matter of serious prayer and seeking.”

With that, Zeb stood up and left the room. He tried to do it courteously, but he wasn’t sure he succeeded. He just knew he couldn’t waste time this way for another minute.

“Well,” said the head elder after Zeb had left, “what should we do?”

Discover more from The Jevlir Caravansary

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.