Tlisli – A Lesson in Geography and Politics

The commercial riverboat looked a bit odd to Tlisli, who had grown up with canoes and small boats made of skins. This one was made of wood and looked heavy to her. Besides a bank of oars on either side, it had a single square sail, which was furled. While she could see men sitting on the benches, no oars were out. Since she had never been in a boat with a rudder, it felt odd and somewhat dangerous.

Azzesh, it seemed, had friends here too, and she found that she was invited to lunch with the owner of the vessel, one named Aterin. She was surprised that he appeared racially to look more like her than the lighter skinned Inraline. She had quickly gotten the idea that the Inraline related to the natives here much as the Grand Emperor’s people did to the citizens of her home town, Ixtlen.

“You look surprised,” said Aterin, again surprising Tlisli. She didn’t realize she had let her emotion show on her face.

“Forgive me if this is rude,” she said, “but you appear to be as native as me, yet you’re owner of this boat. How is this possible?”

“Well, actually, I’m owner of many boats,” said Aterin, as Azzesh chuckled. I run a trading company both up and down the river and and along the coast. I have several vessels that are sea-going ships for the coastal trade, and even one that makes the run from here to Terinor in Inralin itself.”

“So a native can be a person of power and substance?” Tlisli ignored Azzesh’s laughing.

“Well, yes, but that’s not the issue here. I’m a full citizen of Inralin by birth. Those born in the colony of Tevelin—and you should learn to distinguish the city from the colony—are full citizens of the kingdom. My parents were citizens as well. But a native, as you put it, can own a business here as well.”

He paused a moment. “Azzesh here is as native as it gets, more so than you or I—by ancestry, of course—yet she is a citizen by virtue of residency and service to the governor and crown.”

Tlisli tried, but failed, to conceal her shock. Tlazil as full citizens? How could that be? They were primitives. Well, except for Azzesh.

The subject of her thoughts locked eyes with her as Tlisli came to that point. “Yes, small human, unsuitable even for a good lunch, Tlazil. Any Tlazil who will obey the laws (within reason), and become a part of society, can become a citizen. The Inralin government is very open.”

“You were thinking of Azzesh here as some sort of exception,” said Aterin.

“I wasn’t thinking, I guess,” said Tlisli.

“Indeed, it is your great flaw, other than being too stringy and bland to make a good lunch,” said Azzesh.

“Well,” continued Aterin, “Azzesh is indeed an exception to many rules. But those rules would apply to anyone. Azzesh is luckier than most, stronger than most, and really quite intelligent.” He paused. “Almost intelligent enough not to eat humans for lunch.”

Azzesh just laughed.

Tlisli was anxious to change the subject. “How long will it take to get to the city?” she asked.

“Well,” said Aterin, “I would expect it to take a week, perhaps a little longer.”

“Are we moving that slowly?” asked Tlisli. “I thought we were less than 200 kilometers from the city, and that it would take a couple of days just flowing with the current. I was a bit surprised that we were using neither sails nor oars.”

Aterin looked at her for a moment. “I’m hoping,” he said slowly, “that you understand that the reason we’re not using this square sail is that the wind is blowing almost directly upstream, a truly wonderful situation if one is sailing upstream, but somewhat of an impediment if one is going downstream at the time.” He licked his finger and held it up into the wind, looking at it judiciously as though judging whether he could make use of the sail.

“Yes, I know that,” said Tlisli. Azzesh snorted. “What I don’t understand,” she continued, “is why we aren’t using oars either. I would have assumed we would normally use one or the other.”

“What’s the hurry?” asked Aterin. “I prefer to keep my employees happy, and the oarsmen are happier when their work load is more reasonable. So I use them when I need the speed, and not so much when I don’t. They’re useful for loading and unloading cargo in any case. Right now, I will get to the next town well before my next appointment without the oars, so speeding up accomplishes nothing. And the reason we will take a week is that we will make several stops along the way, all while not hurrying.”

“I know I’m going to sound stupid,” said Tlisli, “but I’m used to that. You mean the people who row your boat and load the cargo aren’t slaves?”

Azzesh snorted again.

“No,” said Aterin, “they aren’t. In fact, slavery is illegal in all Inraline possessions.”

“It was not in my city,” said Tlisli. “It’s not in the Grand Empire. I hadn’t ever heard of a place where there are no slaves. What do you do with them? I mean, with the people who would be slaves? What do they do?”

“Well, normally I employ them, pay them their wages, and get much more value from their work than any slave owner would,” said Aterin. He was looking at her without any sort of condemnation or condescension, very much unlike the way Azzesh would.

“Inralin is a very different place,” she said after a moment.

“Well, perhaps,” said Azzesh, “though I should point out that in the Keretian colonies and Marahuatec there is no slavery either. You humans here in Porana inherited some good things from the Tlazil Empire. Too bad you chose to keep the bad as well. Slavery is bad. I’m a realist, not a moralist. It’s not that I think slavery is wrong. I would, after all, go further, and eat you for lunch were you not bland and stringy. It’s that I think those countries that practice slavery eventually pay for it in efficiency. The Grand Empire has found itself blocked by smaller but more efficient societies on three sides so far.” Tlisli continued to note how much more sophisticate the Tlazil sounded now that she was in a more sophisticated society.

“I thought the Grand Empire’s armies were essentially unstoppable. When they arrive you will eventually fall.”

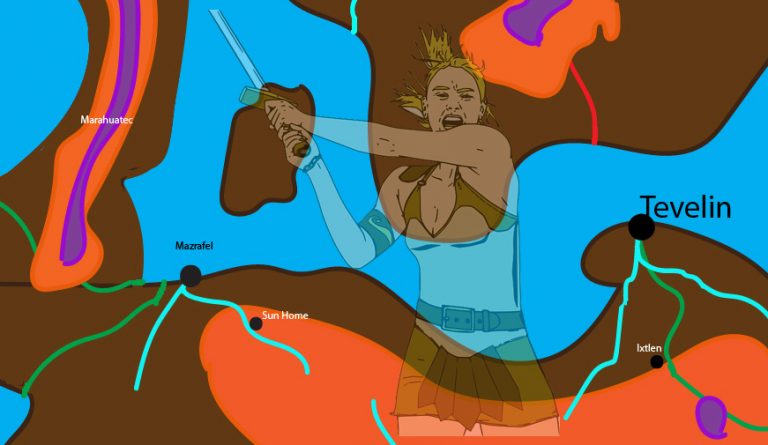

“You haven’t seen very many armies, small human. The armies of Marahuatec to the north and northwest stopped them cold. The Keretian colony of Mazrafel holds them to the north, and the alliance around Qenixtlan [See We Have Always Failed] holds them to the south and west. The sheer weight and size of the jungle holds them to the south. So now they are coming east.” Azzesh rattled off a list of countries and cities with ease.

“So isn’t it critical that we move rapidly to reinforce the fort if they’re coming east?” asked Tlisli.

“No,” said Aterin laughing. “Orlin may think the most important thing is to guard his fort, and since he’s the fort commander, that’s not such a bad attitude for him to have, but two points: 1) The Grand Emperor’s troops are nowhere near ready to attack the fort, and 2) It would do them little good if they did.”

That left Tlisli to wonder just how a fort like the one she’d seen could be unimportant as a target.

[Previous episode] [Next episode]

(To be continued. The “Next episode” link will be made live when the next episode is posted.)

Note: For those who pay attention to languages in fiction, while I have stolen phonemes from some ancient Central American languages, the language spoken by Tlisli is not in any way related. If I manage to match a lexeme in those languages it is entirely unintentional and should not be considered relevant.

Copyright © 2017, Henry E. Neufeld. All rights reserved.

Discover more from The Jevlir Caravansary

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[continued from Tlisli – A Lesson in Geography and Politics]

After a few moments of silence, Tlisli worked up the courage to ask another question. “Why would taking the fort do the Grand Empire little good?”

“Good question! For the same reason that it would be hard for them to actually take it. Clearing the town would be easy, but the fort is, as you have noted, not that far up the river, and the Inralin Navy is pretty much without peer, at least in these waters. So they would take the town itself back quickly. At the same time taking the fortress would place a relatively small number of troops out at the far end of a very tenuous supply line with logistics that can be cut easily by those same troops. How many troops did they have when they attacked Ixtlen?”

“I heard it was a couple thousand. I don’t remember precisely.”

“And how many do you suppose they left home with?”

“I have no idea. Nobody discussed that.”

“That is as I expected. Rulers of a city state are not used to dealing with the logistics of an extended campaign. Ixtlen is more than 1500 kilometers from the nearest Grand Empire outpost. So they have to deal with losses along the way, with setting up outposts, and establishing some sort of a supply and communications chain. My guess is that the overall expedition started with 10 times that many.”

“So if the city had decided to resist, we might well have succeeded. There weren’t necessarily tens of thousands more troops just around the corner.”

Azzesh laughed.

“Hardly!” said Aterin. “I have no idea how your guard would have done against a couple thousand troops. Make no mistake, Grand Empire troops are well-trained. At the same time they are not extraordinarily well-equipped, and they are loyal as long as there are officers and enforcers in range.”

“Of course, once they had established a route suitable for communications and resupply, they could have followed up with more troops. Travel time would only be a couple of months,” said Tlisli.

“Very good!” said Aterin. “You know how to think about these things!”

“It would take considerably less time to bring troops from Ixtlen to Tevelin or to the fort.”

“True, but first they must be at Ixtlen. Which is the point of taking the city. Once they have built up their troops there, they will move south.”

“But they’ll eventually do that, and they will threaten Tevelin.”

“Again, true, and so we will warn the authorities, and they will prepare. One should note that sailing from Terinor to Tevelin takes less time that the fastest conceivable transit from Ixtlen to Tevelin.”

“Wow!” said Tlisli.

“You’ve lived inland all your life. You have never seen an Inraline sailing ship. Fortunately, the Grand Emperor doesn’t really understand sea power either.”

“Oh, I’d say he understands it quite well,” said Azzesh, cutting in.

“How’s that?” asked Aterin.

“He shows that he understands it by what he’s obviously attempting here.”

“What’s that?”

“He means to take Tevelin and make it a Grand Empire base. It may look like an impossible task to you, and he’s certainly not going to move quickly as Tlisli here says.” She turned to Tlisli. “Besides being stringy and bland and not thinking enough you are filled with romantic ideas of single combat and decisive, swift strokes that decide an issue quickly. Your addled brain thinks in terms of heroes, villains, and glory. Yet perhaps Azzesh’s efforts are not totally wasted and you may come to understand reality enough so that you understand that war is a nasty, brutal, never-ending business.”

“The current Grand Emperor’s grandfather started the expansion of the Grand Empire,” said Aterin. “At the time, Sun Home was little larger than Ixtlen is now.”

“While his troops, and girls such as you think in terms of days and weeks, he doesn’t even think in terms of months,” said Azzesh. “He thinks in terms of years and decades.”

“The process,” pronounced Aterin in a tone intended to end a topic, “is to make Tevelin unprofitable so that in the end Inralin will be happy to let it go. Then he will use Tevelin to cut off the Keretians at Mazrafel and to harass the Marahuatecan navy.”

“And you just go on engaging in commerce?” asked Tlisli.

“Why of course? Do you have a better idea?”

“You must require a large number of guards.”

“Absolutely. Which leads me to you.”

Azzesh started to interrupt him, but Aterin waved her to silence. That he could do so was astonishing to Tlisli. “I will let her know how things are. I won’t try to cheat her because she’s naive.”

He looked directly at Tlisli. “You’re going to need to decide what you do next. You’ll need a way to make a living. Did you have any plans?”

“Not really,” said Tlisli. “I don’t really have any skills. Girls weren’t expected to have careers in Ixtlen. It wasn’t so brutally enforced as in the Grand Empire, but it was still true.”

“Actually,” Aterin replied, “you do have one skill set. This conversation wasn’t entirely idle. I wanted to see if you could carry on a conversation about politics and commerce. Of course, we’ve only touched a few minor concepts. You’re not well informed, but you do have the ability to follow the conversation. But that isn’t the skill set I’m talking about. You traveled for weeks with Azzesh, and she hasn’t yet eaten you for lunch. That’s an indicator of skill. I’m hardly going to hire you at the wages of a veteran of the Governor’s Guard, but you are well above the skill level of the average new hire I get as a guard.”

“I hadn’t thought …”

“Just so,” said Azzesh.

“How could you have?” said Aterin. “Here’s what I propose. You will serve with my guard during this trip and my stops while we go to Tevelin, and then I will make an offer. I would expect that I will offer more than you can make as, say, a barmaid, yet less that I would offer someone with actual military experience. I get someone with better skills because I trust Azzesh’s word. She recommends you, despite her insults. You get a bit more pay than you could get otherwise. Over time, you can get to the point where your value and your pay match more closely.”

“So you’re paying me less than you think my skills would be worth because I don’t have formal proof.”

“Yes, and because you don’t have the level of experience of others. On the other hand, because you grew up in a home involved in politics and commerce, you do have some acquaintance with how these things work.”

“That makes sense to me,” said Tlisli. “I would have been suspicious had you offered me some sort of full wages.” She paused then laughed. “Well, I would have been suspicious after I found out what normal wages were.”

“So do we have a deal?”

“Yes,” said Tlisli.

“Very well, let me introduce you to my ship’s guard commander, and she’ll put you to work.” He noticed her surprise. “Yes, the captain is a she,” he said.

[Previous episode] [Next episode]